Crevasse rescue is the process of retrieving a climber from a crevasse in a glacier. Because of the frequency with which climbers break through the snow over and thus ‘bridging’ a crevasse and fall in, crevasse rescue technique is a standard part of climbing education. Wikipedia

At 10,781 feet above sea level Mount Baker, a dormant volcano in Washington State (last eruption Fall 1880) has eleven named glaciers. The Coleman glacier wends it’s way down to the mountain’s lower reaches with the terminus (sometimes called the toe or snout) located at about the 5,300 foot level. Unfortunately like most all glaciers it and the other ten are steadily receding because of global warming.

I participated many years ago in a basic mountaineering course spread over six early spring weekends and organized by BCMC the British Columbia Mountaineering Club. The Coleman glacier was the site of one of the trips. We drove from Vancouver, BC to the rendez-vous at about 4,600 ft where the road terminated. Following a trail from there, we climbed through sub-alpine forest about a further 1,000 feet to the (long since removed) Kulshan cabin. Some people elected to sleep overnight in the cabin others, myself included, chose to sleep outside on the snow in our mountain tents. My sleeping bag was rated to be good for minus 20 degrees centigrade. Regardless, I almost froze to death. I have never been so cold in my life before or since.

The training goals for this trip did not include climbing the mountain but were instead focused on learning glacier travel techniques including roping up and the use of crampons and ice axes. The latter have multiple purposes including self arrest in the event of a fall on steep snow or ice. This arrest technique is crucial to safety, especially when roped with others. A tragedy unfolding high on the mountain not far from the summit and unbeknownst to us at the time was to underline this point.

From the cabin we headed, via the Heliotrope Ridge trail, for the Coleman glacier about 700 feet above us. That ridge is the quickest route in the area leading to a glacier. After about four kilometers it reaches the glacier’s terminus. The trail is also the beginning of a popular route to Mt. Baker’s summit, the Coleman/Deming route.

Mountaineering, especially above the tree line and hence by definition in the alpine zone, can be dangerous at any time under virtually any climatic conditions, an accepted part of the challenge. Beyond tree line, especially during the spring thaw, life threatening dangers await the unwary and the unprepared. Slowly melting and subliming (see note below) snow fields become unstable and prone to avalanche as do wind formed cornices on the leeward side of ridges and summits. On the glaciers, the snow bridges hiding crevasses from view soften and collapse, not infrequently under the weight of unsuspecting climbers. Glacier travel is not for the faint of heart and a knowledge of rescue techniques along with acquired and practiced skills therein must be mandated.

To hear the first high pitched rifle-like cracking sound at the very moment an avalanche signals its onslaught is to hear the starting gun of the Gods. It is worth being God fearing. From a safe distance, I have heard that sound and watched the ensuing result in the British Columbia Coastal mountains and in the Rockies. The crack is soon followed by a low frequency deep throated and intense rumbling which builds, often slowly at first, before quickening into a roaring crescendo as snow piles on top of snow with nowhere to go but down the slopes, couloirs, cirques and gullies, building up momentum second by second clearing anything and most everything in it’s path.

We encountered no collapsing snow bridges over crevasses. However there are plenty of other ways to enter a crevasse willingly or otherwise. Glancing around the one that I found myself in, I remember being immediately awed by the stunningly intense deep blue and sheer beauty of the ice. The deeper down into the crevasse I went, the richer the hue and the more spectacular and translucent the ice became. I eventually reached the more or less level floor.

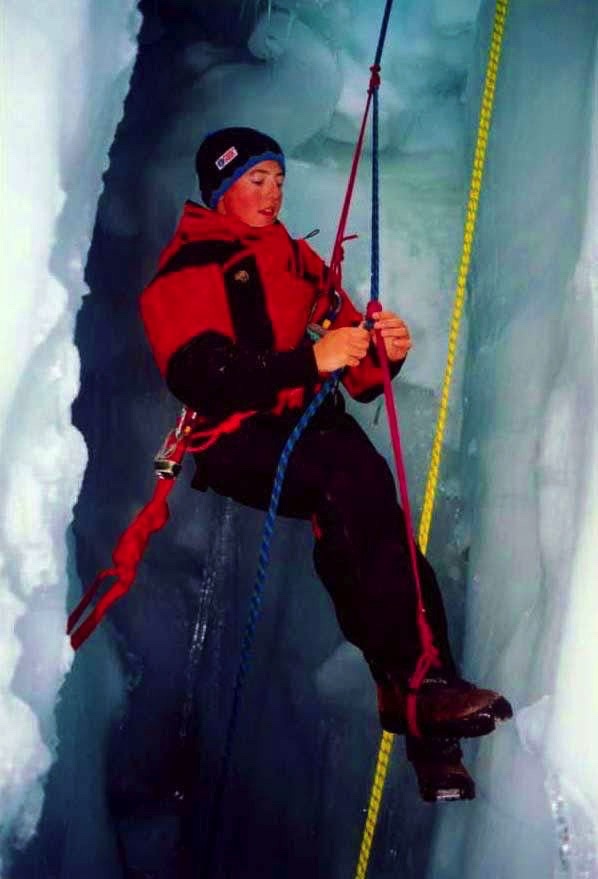

Crevasses can be up to about 45 metres (150 feet) deep and about 20 metres (65 feet wide). The one I was in was about eight or 10 metres (30 feet) deep and about 3 metres (10 feet) wide. By what unforeseen stroke of fortune did I get there? Even though this was a basic course, because of it’s importance the BCMC’s training goals it turned out included crevasse rescue. With good reason. Many crevasse rescues are attempted each year world wide. Being the smallest and lightest of our group, I was chosen as the guinea pig to be lowered into the crevasse on a climbing rope and instructed for the benefit of all of us on how to get out using a technique called prusiking.

Developed in 1931 by an Austrian mountaineer Dr. Karl Prusik (hence the prusik knot and prusiking) technically a hitch, the ‘knot’ is formed with a loop of 5 or 6mm cord. The ends of about 1.5 to 2 metres of cord are tied together with a double or triple fisherman’s knot. The loop is then wrapped three to five times around a climbing rope and the tied ends taken out of the last loop to form a barrel around the rope. An (unweighted) loop is pushed up the rope and the one below is weighted by placing one foot in it, the friction then created on the climbing rope by the latter prevents its descent. One can then take a step vertically into the upper loop by transferring one’s weight to it, thus it then stays in place and the lower one can be released and also moved further up the rope. The two loops are thus used alternately. Of course the technique relies on would be rescuers lowering a rope (and if need be Prusik loops) however ideally loops should always be carried on glaciers by all climbers.

Prusiking it turned out is quite difficult and time consuming. However I did manage to climb some way up the rope thus demonstrating the technique and proving the point. To save time, I was finally hauled out by the considerable man (and woman) power available at the crevasse’s edge. Do not even think of walking on a glacier alone. Be well separated when roped up and be very sure that all in the party are trained to make ice axe arrests, to prusik and to rappel. (Descend under control on a rope.)

The earlier referenced tragedy that unfolded high on the mountain even as we and equally oblivious others were on various parts of it, did not involve a crevasse situation. Four climbers from Vancouver lost their lives near the summit that day. They had set out to summit and then ski down the mountain. Still ascending and all four tied in on one rope, they were swept over a cliff. It was presumed one or more of them had a fall and that the others were unable to effect an arrest via ice axe or otherwise.

Over the six weekends of the course, along with instructing us in crevasse rescue we were taught rapelling along with snow, rock and ice climbing and descending techniques. BCMC also drilled into us the crucial importance of letting someone know where we would be headed and when we would be returning. Also the importance of confirming with them one’s safe return. They also stressed the need to carry comprehensive current generation safety and overnight survival equipment. (and don’t expect a cell signal inside a crevasse!!).

NOTE: Sublimation is the transition of a substance directly from the solid to the gas state, without passing through the liquid state.

For information on Canadian mountain and back country travel safety precautions and survival equipment must haves, see:

www.adventuresmart.ca and/or www.northshorerescue.com

If bears are likely in the area you will be in, take bear spray along with bear bells and hope the bear is a black bear and not a grizzly!