Some years ago an early morning phone call brought devastating news to me of an aviation ‘incident’ to use the classic softening euphemism favoured by authorities of various and sundry stripes. Responding right away I drove to Delta Air Park (now Delta Heritage Air Park) * twenty-five kilometres south of Vancouver, Canada. The small airfield has but a single east west grass runway or strip if you will. It does not have a control tower hence flying safety is entirely dependent on a see and be seen mentality. The call was from one of my two co-owners of a light aircraft an Aeronca Champion which we flew out of the air park.

On arrival at the field I could not believe the complete destruction that had befallen our airplane. What had been a fine airworthy example of Aeronca’s answer to Piper Aircraft’s ubiquitous J3 Cub, our 1947 Aeronca Champ wasn’t so much down, she was upside down, a total wreck amid an extensive field of various and sundry debris with the heavy sickening aroma of leaked fuel prominent in the air. At least there had been no fire and nobody had been hurt. The plane was some considerable distance from our assigned tie down location. How did it get there? Why was she inverted? Who and what had triggered the inversion causing our airplane to be damaged very obviously beyond repair?

Learning to fly was a dream I had cherished since my childhood in Britain. As a pre-teens child, when visiting my maternal grand parents who lived very close to a Royal Air Force base, I would watch the early examples of UK jet fighters in the 1950s such as Britain’s first jet fighter the Gloucester Meteor along with Hawker Hunters, Vampires, and Gloucester Javelins. They were clearly training flights going through it seemed, most every move in the book. Fortuitously they would often be low and directly over my grandparents house in Northallerton located in the north riding of Yorkshire. I often stayed with them during the school summer holidays and with whom I would spend many happy times.

In my teens, I built and flew model aircraft, gliders and other designs powered by bundles of heavy duty rubber strips attached to a plastic propeller. Power was generated by winding the propeller up by hand. With the propeller then released, the rubber strips would gradually unwind themselves and with a strong simultaneous throw launch, the plane would fly under its self generated propulsion if not for very long.

I was keen to one day pilot if not jet fighters then certainly light aircraft and to travel on the then rapidly developing international airlines. I was not destined to set foot in an airliner it turned out until after, along with my wife I had immigrated to Canada in 1967. Rather than fly we settled instead for a London to Montreal nine day relaxing sojourn aboard an ocean liner. We visited the UK by air three years later flying from Vancouver to London on a non-stretched i.e original passenger capacity Boeing 707. My first flight in an airliner but not my first time flying. We made brief landings for fuel in Iceland out bound and Greenland on return the early passenger jets having limited range. My first flight? When I was twelve or thirteen in the mid 1950s, thanks to a lucky happenstance I flew for the first time by way of a local joy ride.

By pure chance I had discovered there was going to be an airshow in the town I grew up in Barrow-in-Furness Cumbria which didn’t have a public airport and still doesn’t. It did and still does however have a private airfield owned then by the local Vickers-Armstrongs shipyard and now by their successor BAE systems. Periodically royalty and other dignitaries would be flown in to christen and launch, stern first with a bottle of champagne broken over the bow, transoceanic passenger liners such as for example the much beloved SS Oriana. **

Along with ocean liners, the smaller elegant lower passenger capacity precursors of today’s enormous offshore built cruise ships, also built were oil tankers, freighters and at that time diesel electric submarines. Still building subs in Barrow to this day, they have been nuclear powered and nuclear armed for a very long time. At high tide, we would watch the launches from the beaches the ships sliding slowly and majestically down the slipway. The high tides were often greater than thirty feet which they needed to be to launch the larger vessels, the narrow channel into which they were launched between the mainland and nearby Walney Island being quite shallow. Tug boats quickly took charge of the not yet functioning ships. Not yet actually by a long shot at launch.

On the day of that mid-1950s airshow, a schoolmate and I set forth by bicycle for the Walney Island airport formerly the wartime RAF Walney. As the crow flies the airfield was about a mile away from where we lived. To get there however we had to travel about two miles south into town, a mile across town and then across the roughly 500 yards long Jubilee bridge connecting the mainland to the island. Next came a right turn before pedaling about three miles north to the airfield. Walney island is about eleven miles long and mostly about one mile wide. Basically it is a sand bar. The trip took us rather more than an hour the airfield being located at the far northern tip of the island.

Neither of us had been to the airport before or to anywhere near it. After crossing the bridge the initially quite narrow unkempt and potholed road gradually improved. This was fortuitous as we were by then about five miles from home and neither of us had thought to bring a puncture repair kit. It would have been a very long walk home. With the surface eventually completely free from potholes and the road becoming gradually wider we were able to quicken our pace marveling at our good fortune in even finding the right road. About half way on this last leg of the route we heard a strange noise ahead of us getting louder literally by the second as we closed on it. Hard to describe, it sounded we thought like it was probably road repair equipment. Likely a very large drill, a jack hammer or maybe both. Perhaps the road ahead wasn’t so smooth after all.

Were we surprised when a fast moving aircraft suddenly appeared at ground level coming straight at us at high speed. My friend quickly rode to one side, yes of the runway, and I the opposite side both of us falling over the handlebars and diving straight into ditches. Unknowingly albeit foolishly we were on the one and only runway. The aircraft continued its take off run the pilot likely having conniptions at having only just missed us. We sheepishly rode the bikes along the edges of the runway forthwith fortunately finding an aircraft taxi strip exit before encountering anyone or anything that smacked of officialdom. We found the actual road approach to the airfield, paid a small entrance fee and nonchalantly joined the airshow crowd as though nothing had happened.

It did not take us long to notice a sign which read Sightseeing Flights seven and six. Translation: seven shillings and six pence roughly about a third of a pound. Equivalent to perhaps $15 dollars Canadian in today’s present value terms. Ultra cheap even by our money scarce lower working class standards. Between us we had almost no money let alone seven and six each. (There were twenty shillings to the pound, twelve pence to the shilling.) We made the decision to cycle home as fast as possible, plead for the money from our parents to both pairs of which, the amount would have been regarded as considerable. If successful we would then quickly return to the airfield. This we did having succeeded in getting the cash and returning this time, via the correct route.

Pedaling furiously in perhaps an elapsed hour and a half or so we arrived back and bought tickets for a flight. Neither of us had been inside an aircraft. We were hyper excited to say the least. With a number of flights booked ahead of us we went to watch the take offs and landings each flight being about fifteen to twenty minutes. The aircraft? It was a twenty plus years old bi-plane, a twin engine de Havilland Dragonfly Rapide built in Britain during the 1930s. (See the first one of the six photos below.) A short-haul aircraft able to carry eight passengers plus two pilots. Each of the four seats to port and to starboard of the extremely narrow single aisle had a quite large window.

Time flashed by as it often seemed to in youth and soon it was our turn to board. The seats were not assigned it was just first come first served until the eight seats were occupied. We boarded from a door near the tail. From there we had a surprisingly steep climb to the seats. This was long before tricycle undercarriages today’s norm were ubiquitous on commercial passenger aircraft. On the ground the nose of the plane was much higher than the horizontal stabilizer and the tail wheel. (Colloquially a ‘tail dragger’ or ‘stern wheeler’ as an Australian pilot once said to me.) One of the two pilots closed the door of course there not being even one flight attendant. The engines were then started the noise being decidedly loud even at idle. My friend and I were very excited. I’m sure we must have hoped this time there were no cyclists on the runway.

After a garbled departure message from the marginal at best cabin intercom, the throttles were opened and the two engines revved up with a roar as we taxied out on to the runway and started our take off run. After a short distance the tail rose causing the fuselage to become parallel with the runway. The noise increased to a crescendo, the nose lifted slightly and very soon we were off and climbing – we were flying, I was flying. Perhaps, I remember thinking, like my favourite uncle I would one day have a flying license.

In addition to building ships Barrow was then also a steel manufacturing town, steel of course being the primary ship construction material. Steel is made by heating and melting iron ore the latter being surface mined locally. Impurities are removed from the molten ore and carbon added. The process leaves behind a lava like residue called slag for which there aren’t really any uses except occasionally as road fill. Thus it was just piled high, slag upon slag for years on end.

Barrow then had one of the biggest slag banks *** in Europe. It was about half a mile long perhaps two hundred yards wide at its base and had a railway line running the full length of the top which was essentially a narrow flat ridge. Travelling along the ridge on rails, a small narrow gage steam locomotive periodically pushed a wheeled and very large cauldron ahead of it containing red hot molten slag fresh from the steel plant. The engine operator, choosing his spot, could tip the cauldron and thus spill the slag over one side or the other of the bank’s ridge. At night and glowing red hot, it flowed like larva from a volcano as it crept part way down the sides and solidified. It was very spectacular and visible about half a mile distant from our house. No longer in use the steel works having long since been closed down, large parts of the slag bank still remain.

Immediately after take off our pilots headed us guess where, straight for the nearby slag bank the immediate alternative being out over the Irish Sea, not a good idea unless one was bound for the Isle of Man about 100 kms or so away or Ireland about 225 kms away. For the first and it turned out to no surprise, only time, I could look down on the top of the slag bank. It looked more or less like the rest of the massive amorphous grey mass. Barren, lifeless and more than a little foreboding.

After overflying at low altitude both the slag bank and what remained of the steel works site, we were treated to other low level close by and quite stunning aerial views of our town of about 60,000 people. The shipyard with its many huge cranes, our spectacular local red sandstone built town hall, the Furness Abbey ruins built with the same sourced sandstone and dating back to the year 1193, its occupants Cistercian monks and nuns long gone.**** Also visible and distant only about twenty miles away was the much beloved Lake District National Park. Think the poets Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey.

Fifteen minutes or so went by all too quickly, the pilots turned us back towards the airport and to we trusted, a smooth and safe full stall landing which indeed they did. (Ask any passing bird how a full stall landing is done &/or observe one doing so.) Forward located tricycle undercarriage equipped aircraft (most all of them these days) are landed smoothly onto the main landing wheels first, the nose initially held slightly high to hold its wheel(s) off before allowing a slow gentle descent onto the tarmac thus ‘greasing it on’ as they say. No stall necessary. (stalling in an aviation context having of course nothing to do with an engine quitting).

As previously mentioned, about ten years later in 1967 as immigrants to Canada my wife and I arrived by sea disembarking at the port of Montreal. We then set about driving to Vancouver in a small car***** we had brought with us shipboard. This we did over a period of about four weeks pup tent camping all the way. En-route, traveling mostly on the Trans Canada Highway and covering about 3,000 miles or 4,800 kms in total, I saw many large billboards advertising a Cessna Aircraft ‘Learn to Fly’ promotion. Good for anywhere in Canada, the first lesson would be subsidized by Cessna and would cost only $10! Needless to say I made a mental note for future consideration.

It turned out also that the Canadian government would subsidise flying lessons, this to the tune of $100. I thought I had stumbled upon nirvana. I might as well have for myriad reasons, not the least being nation wide egalitarianism. I was once told in the UK in no uncertain terms by a Rolls Royce owning supercilious upper class then boss that “I would have to LEARN to know my place”. Need I say more? Even then in my still teenage mind I already had identified ‘my place’ and it was not within the class divided and obsessed UK. I was already hoping it would be as a Canadian immigrant and eventually citizen. Fortunately and thankfully both came to fruition.

The Canadian Federal Government’s flying license training subsidisation incidentally was because there was then a shortage of commercial airline pilots as opposed to commercial bush pilots. In order to take commercial flying training be it for bush operations or the airlines, the first step is to earn a private flying license.

In my first year in Vancouver after fortuitously landing a decent paying job soon after arrival, I did take advantage of Cessna’s first lesson offer, along with the federal government’s $100. I learned to fly in Canadian designed and built Fleet 80 Canucks (tail draggers to a fault)) and earned my private pilot license. (Single engine land #11499.) In that first year I also bought a racing sailboat, a Shark 24 as in 24 feet long. Financially something had to give. Reluctantly I gave up flying at least for then and focussed on sailing. Years went by until one day a work colleague, an ex British RAF fighter pilot, mentioned that he wanted a couple of partners to buy and share a single engined light aircraft an Aeronca Champ which he had been offered. I became one of the trio and as previously stated the aircraft now lay in pieces at Delta Airpark beyond repair because of, we were to discover, one individual’s appalling customer distain, negligence and his dereliction of duty. That individual was the then Delta Airpark manager.

On inspection we found that our totally wrecked Aeronca Champ C-GHIR, was nowhere near our designated tie down location where we had of course left it the last time it was flown. It certainly had not flown itself to another location on the field but it was a very long way from our tie down. How could this possibly be? Simple. The airport manager, without consulting us had moved it and tied it down in a swamp. There were no other tie downs in that area because it was a swamp. He had done this he said quote ‘as a favour to a friend of his’. That aircraft was safe and secure AT OUR TIE DOWN. A winter gale had come up the previous night. Champs have large wings for their overall size and weight. Air blowing over a wing of course generates lift that is why aircraft fly. (And why sailboats can go to windward given also that the keel limits sideways motion.) The wind had lifted the aircraft clean off the ground complete with its two cement anchors and it had flipped over. Judging by what was left of it, flipped over perhaps more than once.

From the swamp, C-GHIR had taken off for the last time. The risk of which any fool could have foreseen given that her tie down line’s anchors were not remotely adequate to hold her down in a swamp even in a light breeze let alone in a full on winter gale. In her attempt at a take off, the high wind speeds, aided and abetted by the cold and thus particularly dense winter air made especially dense by prevailing record overnight low temperatures, had flipped her over. The wind had then blown her some considerable distance. In doing so, along with self destructing she had considerably damaged another aircraft which was properly and legitimately anchored and tied down well clear of the swamp.

What about our insurance? Here was a classic case of the adage ‘it never rains but it pours’. We were awaiting getting some work done on the engine. While doing so our insurance had expired. So what? We were not going to fly until we knew the engine was back to 100%. What could possibly happen properly ground anchored and tied down at her assigned location as she certainly had been by us her owners?

None of us knew anything about ‘ground only’ insurance. Certainly ground insurance was included with our recently expired regular insurance. The likelihood of a rogue and incompetent airport manager emerging as a risk factor was not something that came naturally to any of our minds. Had it done so, we would certainly have had ground only insurance pending the engine repair. Using my lawyer we did explore various avenues of recompense. All of them led to costs to us much greater than the value of our aircraft. C’est la vie!

* Delta Heratage Air Park web site and cam at: https://www.deltaheritageairpark.org

** Oriana see # note below.

*** Slag bank: Colloquially the word bank in this context simply means hill or pile. See photo below.

**** Cistercian monks: a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns. See my story of June 06, 2019 ‘Furness Abbey’ especially if you like ghosts.

***** An Austin 1100 in the UK, known as an Austin America in Canada. (Don’t ask.) See my story ‘Austin 1100’ April 18, 2019.

# SS Oriana was routinely plying between Australia and Vancouver when we arrived in 1967. I managed to get an invitation to board her at the cruise ship terminal. I was pleased to find and rather proud to read on the prominently displayed highly polished brass builder plaque ‘Built in Barrow-in-Furness.’ She was launched November 3rd 1959. All of us leaving school at sixteen in 1958, many of my school mates went to work in the shipyard and would have had a hand in her construction.

Below: a De Havilland Firefly Rapide biplanefrom the 1930s. My teenage 15 minute first flight was aboard one.

Below a Fleet 80 Canuck. The two seats side by side. The type I flew to earn my flying license.

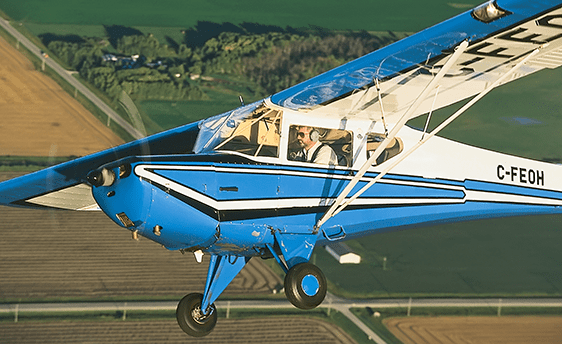

Below an Aeronca Champion. (not ours.) Ours was all yellow except for a blue nose.

Note the tandem seating.

Below the current (April 2022) scene at Delta Heritage Airpark. See link to the website and webcam above at the first asterisk (*)

Below an aerial view from over the airpark. Note the grass runway. Unlike asphalt, Grass is quite ‘forgiving’ if one lands perhaps a touch hard. Note also the dike. The tide is out.

With no electric starter on the Champ a friend with a Harvard, another ex-military fighter pilot and also based at the airpark, taught me the military technique way to safely ‘swing the prop’ to start our engine. Not for the faint hearted. (Rule # 1. Always tie the tail down first!) Nor also for the faint hearted was flying the Champ around with no radio and sometimes over the ocean the airpark being literally on the coast. (The tide is out in the above photo with a dyke visible.) Without a radio, my flight plan notification system was: just prior to take off to phone and tell a friend roughly where I would be flying. I phoned in again on landing to ‘close the flight plan’.

My ‘swinging the Champ’s prop to safely start the engine 101’ instructor friend took me for a ride in his vintage Harvard one day. We were inverted for quite some time with the canopy wide open. Seated of course in the back seat, I remember wondering if the seat belts were original. He did close the canopy prior to doing a loop! Below, here is a thumbnail of a Harvard. (Also a tail dragger. Main undercarriage is just retracting after take off.)

And finally FYI:

The Barrow Hematite Steel Company Limited was a major iron and steel producer based in Barrow-in-Furness, Lancashire (now Cumbria) between 1859 and 1963. At the turn of the 20th-century and the Technological Revolution it operated the largest steel mill in the world.

Upon researching for this story, I discovered that Barrow at the end of the 19th century had the largest steel mill in the world. I suspect the slag bank was thus by definition also a contender for the largest. It was and still is apparently, very massive. Below is a photo of a ‘small’ part of it. The Irish sea abutting it likely at high tide.

I also discovered that present day Barrow has the second largest wind farm in the world. Oy Vay.

Certainly they get a lot of wind off the Irish sea and the inshore waters are very shallow hence good for implanting wind vane towers. The world’s largest wind farm Hornse 2 is located off Britain’s East coast also with shallow and windy waters.